Weaponizing Uninstallers! A new attack surface?

Backstory

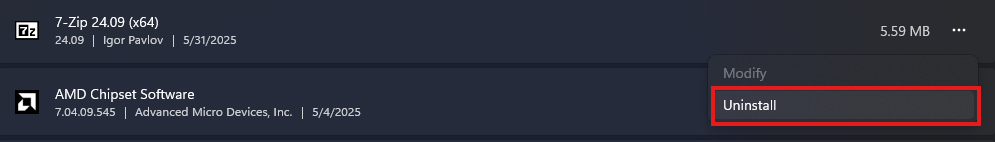

So, there I was… uninstalling some bloated third-party software I had installed a while ago (the kind you forget about until it starts slowing things down). I clicked the usual “Uninstall” button, and that’s when I paused. I started wondering — what really happens when you uninstall software on Windows?

For most apps, clicking “Uninstall” doesn’t delete files directly. Instead, it runs a program that the software developer includes during installation — the uninstaller. This small program removes files, registry entries, and other leftover data.

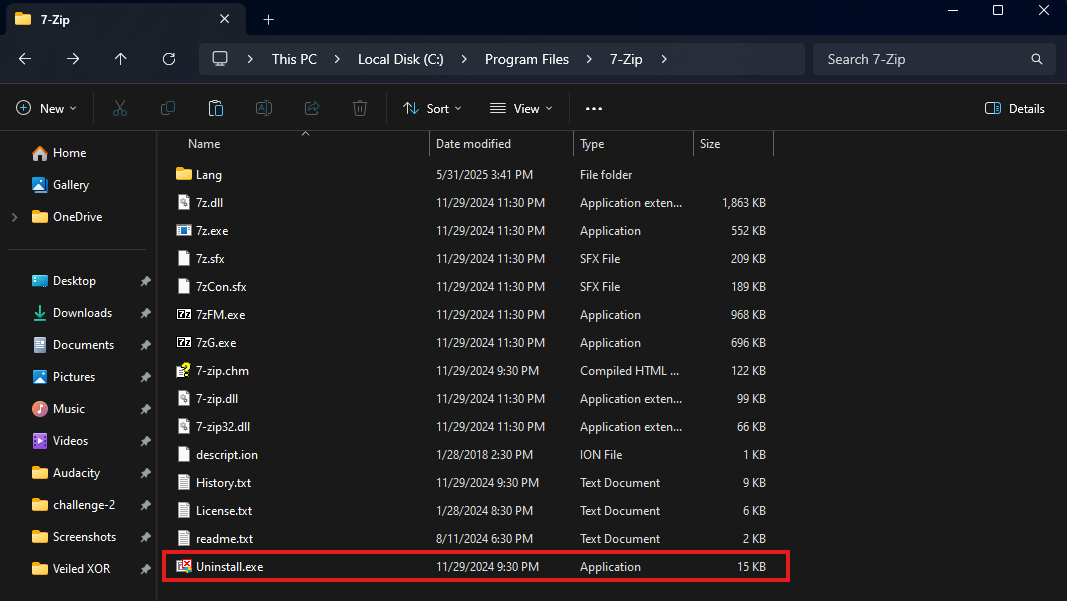

If it’s a Windows Store app, the process is built into the OS. But if it’s third-party software, Windows just runs the Uninstaller shipped by the developer. For example, 7-Zip installs its uninstaller here:

A New Attack Vector?

That got me thinking… we’ve all seen research on how malware can be hidden in installers, or injected into running applications. But what about the uninstaller?

It’s such a rarely used, dormant part of the software — what if someone modified it and placed a backdoor inside it? Sounds unusual? That’s what makes it interesting.

Why the Uninstaller?

Here are a few solid reasons why this technique could be a game-changer:

- Dormant for a long time: Nobody touches uninstallers until the software is being removed. That could be months after installation, making it a perfect hiding spot.

- Triggered by the System: You don’t need to run the uninstaller manually — Windows does it for you when you click “Uninstall” button.

- Elevated privileges: Many uninstallers run with admin rights so they can clean registry keys and system files.

- Under the radar: Most EDRs and AV solutions monitor installers and runtime behaviour. But uninstallers? Not so much.

Proof of Concept: Modifying 7-Zip’s Uninstaller

To demonstrate the concept, I chose one of the simplest and most widely used open-source programs: 7-Zip. It has a very basic uninstaller that you can find in: C:\Program Files\7-Zip\Uninstall.exe Let’s dive in and see how we can backdoor it.

Setting Up the Environment

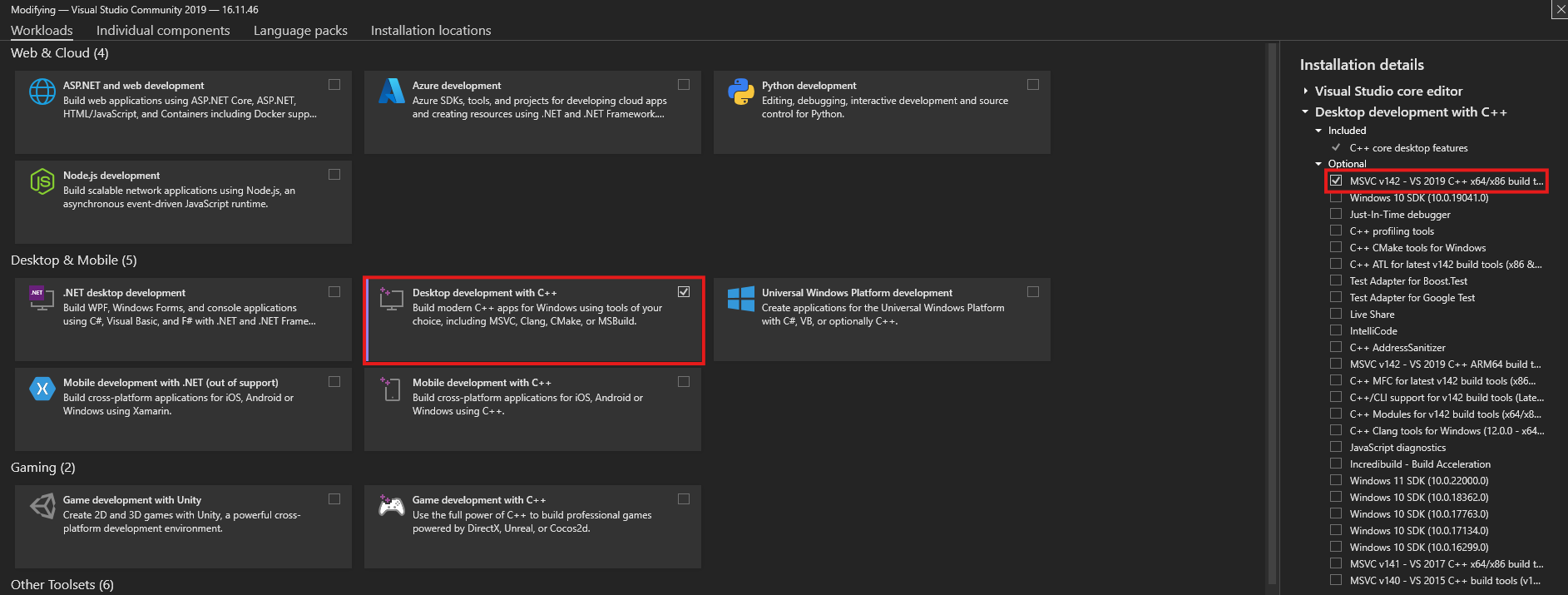

To get started, I needed to rebuild 7-Zip from source. Here’s the setup I used:

- Windows 11 VM

- Visual Studio with Desktop development with C++ Workload

- 7-Zip source code from the official Downloads page

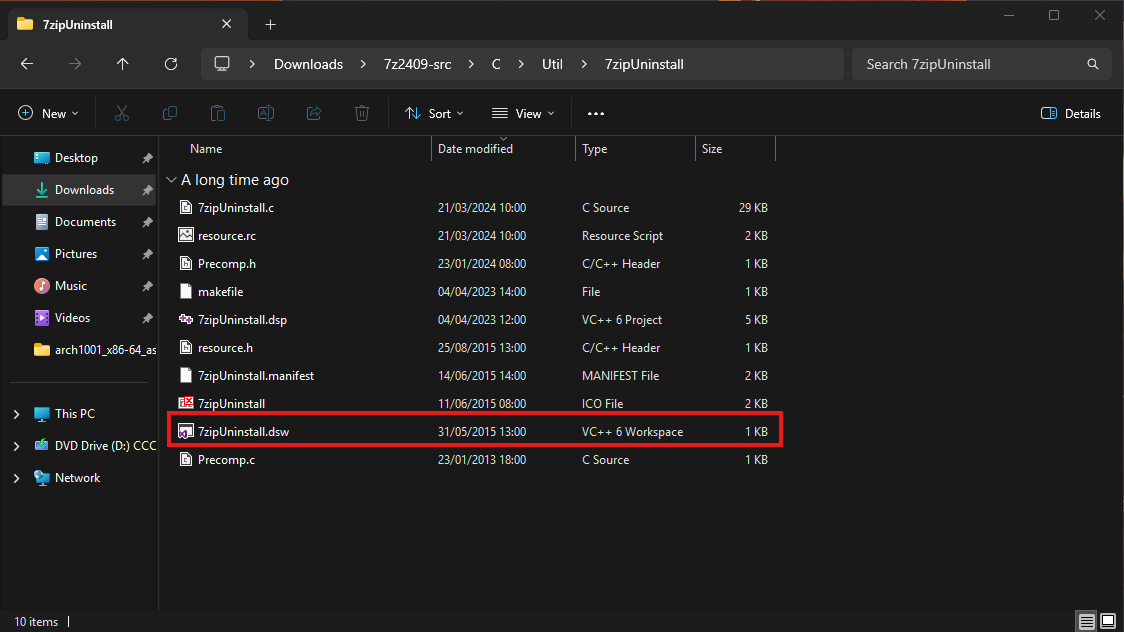

After downloading and extracting the source, I opened the uninstaller code located in:

7z2409-src\C\Util\7zipUninstall There, We can find a .dsw workspace file — this opens easily in Visual Studio.

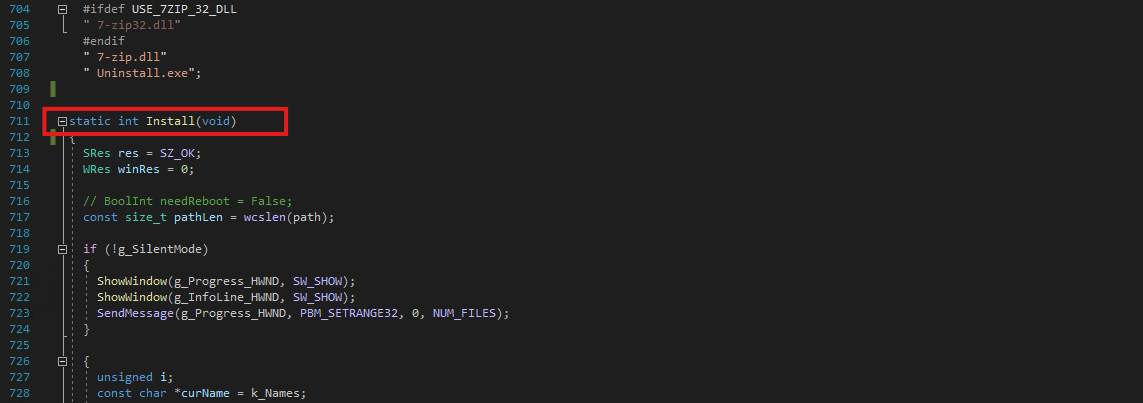

Inside 7zipUninstall.c, I found the main uninstall logic. Perfect spot to inject a small payload.

Adding the backdoor

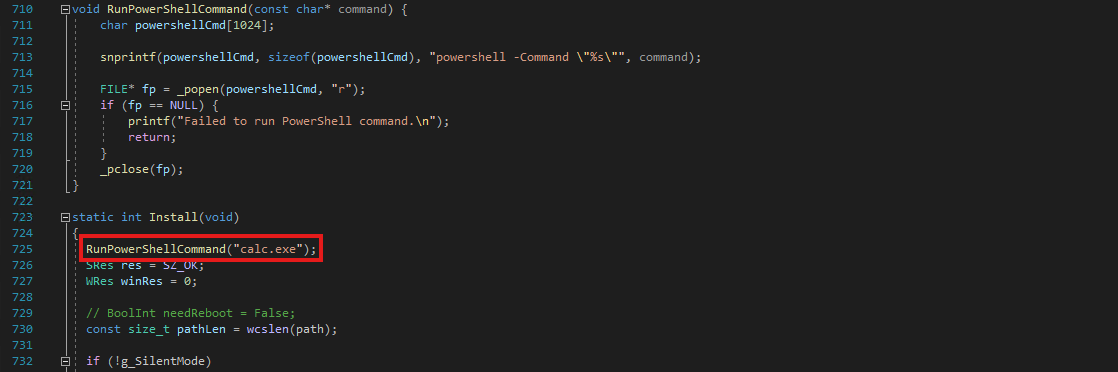

I added a small function that runs a PowerShell command. It uses _popen to call PowerShell from C. Here’s the code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void RunPowerShellCommand(const char* command) {

char powershellCmd[1024];

snprintf(powershellCmd, sizeof(powershellCmd), "powershell -Command \"%s\"", command);

FILE* fp = _popen(powershellCmd, "r");

if (fp == NULL) {

printf("Failed to run PowerShell command.\n");

return;

}

_pclose(fp);

}

You can insert this just before or after the original uninstall logic. It could:

- Open a reverse shell

- Create a hidden user

- Drop a malicious file

- Or anything else your payload needs to do

Yes, this simple function is our backdoor.

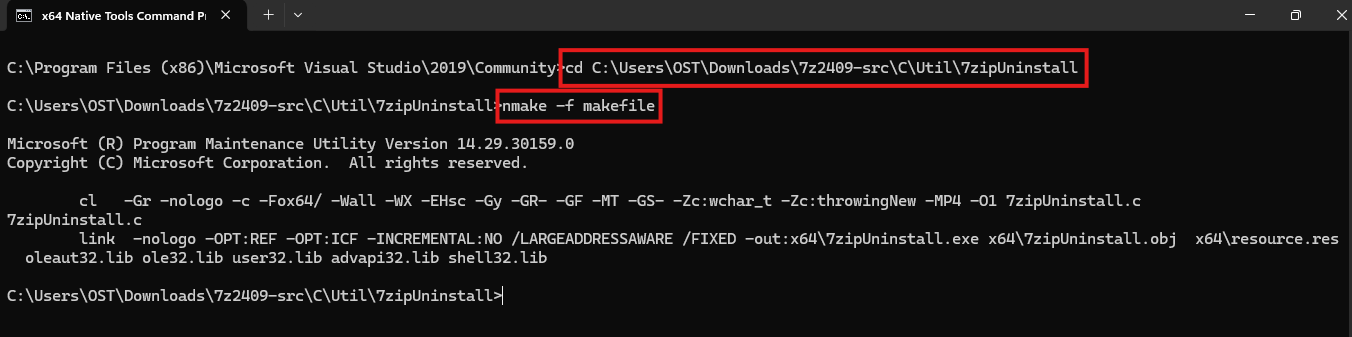

Building and Replacing

After adding the payload, I compiled the modified uninstaller using the x64 Native Tools Command Prompt. Once built, I simply replaced the original Uninstall.exe in the 7-Zip install folder with my backdoored version. Note : An attacker could also bundle the backdoored uninstaller inside the original installer. I didn’t do that here — this was just a proof of concept.

Final Demo

Now, when a user clicks “Uninstall” from the Control Panel/Add or Remove Programs, Windows executes my backdoored uninstaller — and the payload runs silently in the background.

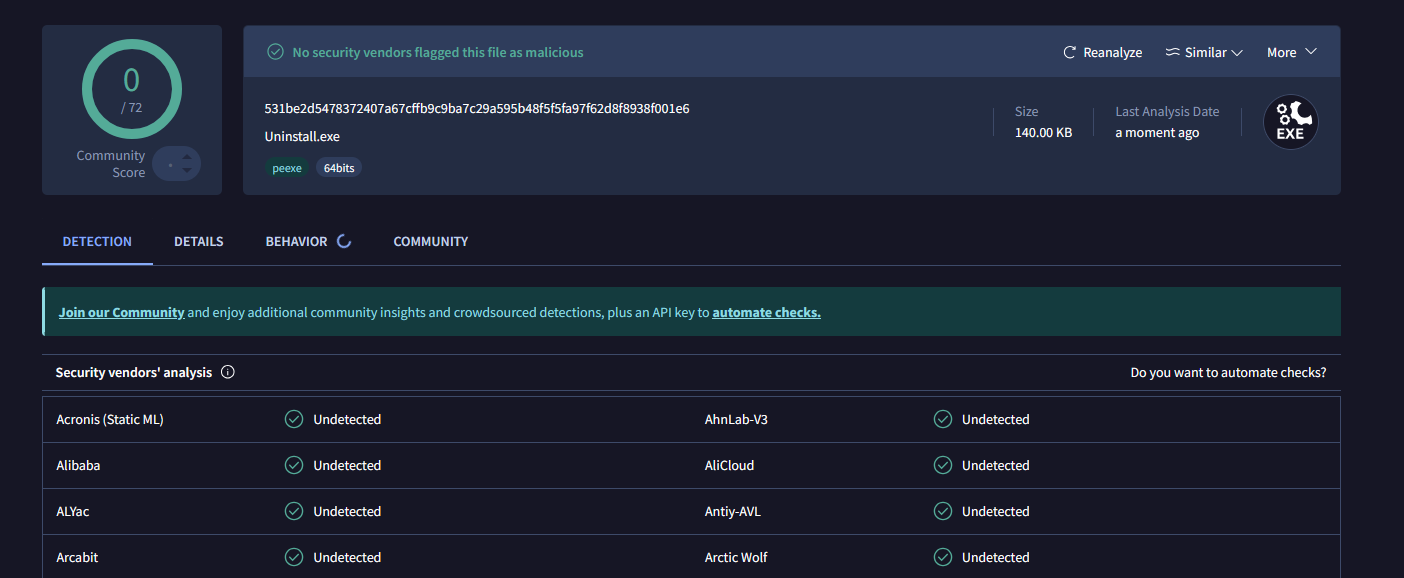

And No matter which payload I used (Even the malicious one’s), VirusTotal consistently showed 0/72 detections.

Conclusion

The uninstaller is a blind spot. It’s assumed safe. It runs late in the software lifecycle, and most tools don’t watch it closely. That’s what makes it useful for attackers. This technique doesn’t rely on user interaction beyond clicking “Uninstall.” It also shows how something as boring as an uninstall button can become a way in.

What Next !?

I’ll be exploring how other popular software handles uninstallation, Would love to hear your thoughts. Have you ever looked at what your uninstallers are really doing?